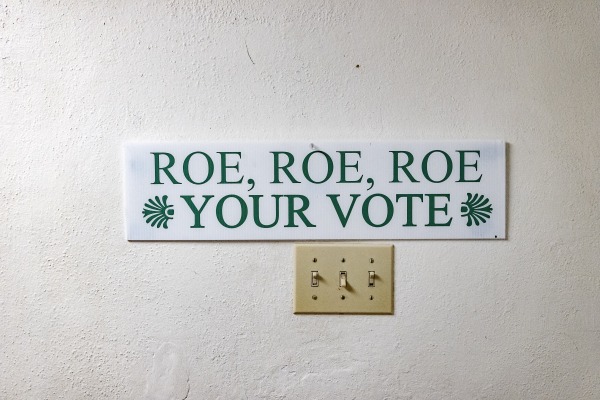

(Rachel Treisman – NPR) – Following President-elect Trump’s victory — which was fueled by male voters and to many looked like a referendum on reproductive rights — some young American women are talking about boycotting men.

(Rachel Treisman – NPR) – Following President-elect Trump’s victory — which was fueled by male voters and to many looked like a referendum on reproductive rights — some young American women are talking about boycotting men.

The idea comes from the South Korean movement known as 4B, or the 4 No’s (bi means “not” in Korean). It calls for the refusal of dating men (biyeonae), sexual relationships with men (bisekseu), heterosexual marriage (bihon) and childbirth (bichulsan).

Interest in the 4B movement has surged in the days since the election, with Google searches spiking and the hashtag taking off on social media. Scores of young women are exploring and promoting the idea in posts on platforms like TikTok and X.

“I think it’s time for American women to participate in our own 4B movement,” one woman posted on TikTok. “If men won’t respect our bodies, they don’t get access to our bodies.”

“Ladies, we need to start considering the 4B movement like the women in South Korea and give America a severely sharp birth rate decline,” reads one tweet with over 470,000 likes. “We can’t let these men have the last laugh… we need to bite back.”

“It’s time to close off your wombs to males,” reads another viral post. “This election proves now more than ever that they hate us & hate us proudly. Do not reward them.”

Several recent tweets from far-right men with large social media followings would seem to illustrate their point.

Nicholas Fuentes, a white nationalist and Holocaust denier — whom Trump was criticized for hosting at a dinner at his Mar-a-Lago resort in 2022 — tweeted, “Your body, my choice. Forever,” as the results turned in Trump’s favor on Election Night. The tweet got 40,000 likes.

Social media users have since noticed a pattern of men commenting that phrase, or similar, on women’s TikTok posts.

Another, Jon Miller, who describes himself as a moderate and “fair & balanced political commentator,” tweeted on Wednesday, “women threatening sex strikes like LMAO as if you have a say.” The post has gotten over 50 million views, sparked considerable backlash and was appended with a community note clarifying that sex without consent is rape.

Ju Hui Judy Han, a gender studies professor at the University of California Los Angeles who also specializes in Korean studies, says the growing interest in 4B at this moment is understandable.

“Clearly, this is about American women trying to find sources of leverage, sources of empowerment that can, in the short-term, make them feel like they have some agency … in these dire times, with the election and Roe v. Wade behind us,” Han told NPR.

That said, she was surprised to see it take off so suddenly this week, in large part because the movement is so specific to South Korean society and what she describes as its “culture of compulsory marriage” and childbirth.

Where did 4B come from — and could it catch on somewhere else?

For context, gender inequality is deeply rooted in South Korea

Han describes 4B as a relatively small movement that began as an offshoot of the growing feminist movement in South Korea, driven by structural misogyny and gender discrimination.

South Korea ranked 99 out of 146 in the World Economic Forum’s 2024 Global Gender Gap Index, and for decades has had the largest pay gap among the countries in the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) — it was 31 percent in 2021, compared to about 16 percent in the U.S.

The Economist’s glass-ceiling index ranked it the worst OECD country for working women in 2022, in part because of strict maternity leave policies that force many women to choose between career and family. That’s one of the reasons South Korea has the lowest fertility rate in the world, down to 0.78 percent in 2023.

The low fertility rate has been a source of alarm among Korean policymakers, and criticism by anti-feminists who blame 4B and other similar movements, Han says. But she says it would be a stretch to blame 4B for causing the decline in childbirths, and in fact, sees it as a response.

“It’s about young women saying to policymakers: ‘You want us to get married and have children, you have to make this world a better place for us to live,’ ” she said.

President Yoon Suk-yeol, who was elected in 2022, campaigned in part on abolishing the Ministry of Gender Equality and Family, which coordinated and implemented policies promoting women’s rights. That move was condemned by many women in South Korea and human rights groups internationally.

High-profile incidents spurred feminist movements like 4B

A series of events over the past near-decade fueled the South Korean feminist movement and the rise of 4B.

One of them was the 2016 murder of a 23-year-old woman in a public bathroom in Seoul’s central Gangnam Station, which the perpetrator later said he did because “women have always ignored me.”

“A lot of feminists and a lot of women came together and posted sticky notes all over the station talking about their own stories,” says Shruti Sivakumar, an Indiana University senior who is writing her capstone on the 4B movement. “And that was just sort of a reboot, I guess, of feminist activism in Korea.”

Meanwhile, South Korea experienced a rise in what the country calls “digital sex crimes,” with hidden cameras recording women in public areas like bathrooms and changing rooms and uploading the footage to pornographic websites.

Those factors, combined with a presidential corruption scandal in 2016, saw millions of South Koreans protesting in the streets for various causes, Han says, and women’s rights was one of them. Those protests continued in the years that followed as the #MeToo movement took hold in the U.S. and around the world.

There was also a rise in online feminist activism around the same time, including the controversial social movement known as Megalia. Another, called Break the Corset, saw young South Korean women smashing their makeup palettes and cutting their hair short in defiance of beauty standards.

Enter 4B, somewhere around 2019. It doesn’t have an elected leader or membership structure. It spreads on social media and through word of mouth, and there’s no way to know exactly how many women have participated.

“It’s not a church, it’s not a cult. It’s more, I think, kind of a state of mind and a set of priorities,” Han said. “What I think is most important is that it’s about women recognizing that they’re in a collective struggle, and that there’s a collective sense of frustration.”

4B is a commitment not without consequences

Han says given the dire situation in South Korea — including a notably high suicide rate among women in their 20s — the 4B movement isn’t coming from a playful or flippant place.

Similarly, Sivakumar describes it as a “last resort” for women who are trying to disentangle their lives from the patriarchy in the name of lasting social and economic independence.

“It’s not meant to be a movement or a form of activism that you’re able to just pick up for one month and just drop as soon as you find someone that you really like and want to talk to,” she added. “It’s supposed to be sort of a form of sacrifice, that for the rest of your life you’re going to be independent from men.”

That commitment can come with consequences.

Feminists — including 4B participants — in South Korea have faced considerable backlash, especially from men, Han said. For example, the country’s president last year suggested that feminism is to blame for blocking “healthy relationships” between men and women.

Han thinks it likely that American women exploring 4B could see backlash from their immediate circle just for “exercising their right to do these obvious things.”

“Declaring yourself to be a feminist in an anti-feminist world can have consequences,” Han said. “I think any sort of refusal to participate in the status quo could obviously have some negative consequences.”

As some social media users have pointed out, 4B is as much about cutting ties with men as it is supporting other women. Sivakumar says the intended target is women’s autonomy rather than necessarily seeking to punish men, calling it an “individual effort on behalf of women.”

The support of a collective is what makes the movement so powerful, Han said, adding that she hopes it will lead to more hands-on organizing for social change.

“One individual refusing to have sex is just one individual refusing to have sex,” Han said. “But when they recognize other women doing the same thing or wanting to share their frustration and their pursuit of agency in doing something collectively, now that’s a start of something else.”

Could 4B catch on in the U.S.?

Many in the U.S. see Trump’s victory as a referendum on women’s rights.

The former president has been accused of sexual misconduct by dozens of women dating back decades and was found liable for sexual abuse by a jury. Despite saying he opposes a nationwide abortion ban, Trump has bragged about appointing the Supreme Court justices who led to the reversal of Roe. His running mate, Vice President-elect Vance, drew widespread ire for his comments about “childless cat ladies” over the summer.

And Vice President Harris had made protecting abortion rights a central feature of her ultimately unsuccessful campaign to become the first female president.

Trump made narrow gains among both women and men compared to 2020, according to the Associated Press — but won men in every single age group. Exit polls show 55 percent of American men voted for Trump.

“I completely see the appeal right now after the election, I’m just so angry with men as a whole,” said Keara Sullivan, a 25-year-old comedian based in Brooklyn who has been hearing a lot about 4B online in recent days.

Sullivan feels strongly that women “should stop dating and marrying and having sex with men who actively vote against their human rights.” But she has concerns about aspects of the 4B movement, including worrying that women abstaining from sex could be seen as playing right into ultra-conservatives’ wishes.

Even so, Sullivan thinks it’s a good thing that people are talking about a U.S. 4B movement. She’s already seeing women who are not usually outspoken about feminism joining the discourse for the first time — and, like Han, hopes it will lead to more direct action.

“I’m hoping that this newfound sense of solidarity women are finding on social media can propel us into more direct feminist organizing and disruption that makes specific demands of our government,” Sullivan said.